Micro poultry farmers to access $200m, but at steep interest rate

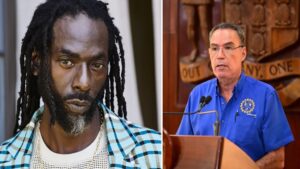

AN audible ripple of discomfort moved through the conference room at the Jamaica Pegasus hotel as Paul Chin, manager for investor relationships at the Development Bank of Jamaica (DBJ), explained that micro poultry farmers are being charged an interest rate of 19 per cent under the bank’s newly launched $1-billion financing facility.

Speaking at the Caribbean Poultry Association’s 8th International Technical Symposium and Exhibition on Tuesday, Chin moved quickly to defend the rate, describing it as a significant improvement over what borrowers typically face in the microfinance space where interest rates can soar as high as 39 per cent.

“Some might say 19.9 per cent is still high — and yes, it is,” Chin acknowledged, speaking to an audience of roughly 250 poultry stakeholders on the opening day of the two-day symposium.

“But in the microfinance space we’re seeing rates that go as high as 39 per cent. What we’ve done is bring that down significantly while maintaining fast, flexible access to capital — and that’s what micro-entrepreneurs care about most,” he continued.

The DBJ’s new poultry financing programme includes $800 million earmarked for large-scale contract farmers and $200 million for micro and backyard operators. While small and medium-size borrowers accessing the DBJ’s funds through banks benefit from interest rates as low as 7.5 per cent, micro-entrepreneurs must apply through accredited microfinance institutions (MFIs), which are allowed to charge up to 19.9 per cent under the terms of the facility.

Chin explained that the disparity is rooted in how the microfinance system works. Microloans are often short-term, labour-intensive, and higher-risk, requiring weekly follow-ups and extensive borrower support — especially in sectors like poultry farming where informal business practices are common.

“These loans demand more administrative oversight, and institutions carry much higher risk,” Chin told the Jamaica Observer in a follow-up interview. “The pandemic really exposed that. Many barbers, hairdressers, and vendors — typical micro clients — saw their income evaporate overnight during lockdowns. That translated into widespread repayment challenges.”

Despite the pushback, Chin argued that the rate was structured with the poultry industry’s dynamics in mind. A typical broiler cycle runs about six weeks, meaning farmers can potentially complete five or six cycles per year.

“A poultry farmer, you can be in and out in six weeks,” Chin noted. “And if you look at 19.9 per cent and you break it down in a six-week cycle you see that it is, in fact, affordable. It gets them to where they want because, in their minds, they are in early, they want to be out early. And they do that cycle — they can borrow five times a year if they are able to do five or six cycles of six-week loans in poultry.”

The facility, introduced at the request of Prime Minister Andrew Holness following the disruption caused by Hurricane Beryl, is part of a wider strategy to strengthen poultry production and ease recurring shortages in the local market. The DBJ is also finalising a second $1-billion tranche that will be distributed through approved financial institutions at a blended interest rate of roughly 8.75 per cent.

Chin said the DBJ has already identified a pipeline of $3.5 billion in poultry-related projects and is in active discussions with several banks and farmers.

“With extended loan tenures of up to 15 years we’ve built a structure that’s sustainable even for borrowers seeking $200 million or more,” he said. “We expect this to improve production capacity, stabilise supply, and support Jamaica’s poultry export ambitions.”