When the Beatles came to America for the first time in 1964, about 4,000 people met them at the airport.

When the Marquis de Lafayette came to America for the last time in 1824, he was met by 80,000 people.

“He really was America’s first rock star,” says Chuck Schwam, executive director of the American Friends of Lafayette.

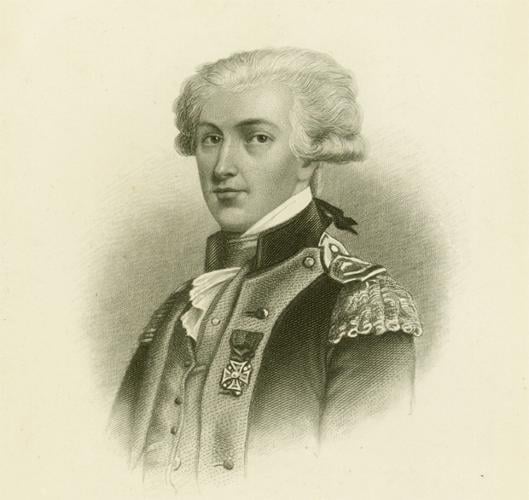

In 1777, during the Revolutionary War, the Marquis de Lafayette, a 19-year-old French nobleman, was made a major general in the American Continental Army.

President James Monroe invited Lafayette to come to the United States to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the American Revolution. He was the last surviving general of that war, and his tour was so successful that it was extended from a planned three months to 13 months.

Celebrated even today as “America’s favorite fighting Frenchman” in the musical “Hamilton,” Lafayette ended up visiting all 24 of the then-existing states, including Illinois and Missouri, traveling a total of 6,000 miles. Everywhere he went, he was cheered and feted.

People are also reading…

- Missouri Senate GOP slams door on Democrats in bid to repeal abortion rights, paid sick leave

- Christopher ‘Kit’ Bond, former Missouri governor and senator, dies at 86

- Could Incarnate Word leave north St. Louis County? School leaders are thinking about it.

- Post Malone, Jelly Roll deliver nearly 5-hour concert that shines and sags at Busch

An actor portraying the Marquis de Lafayette rides through Portsmouth, Virginia, in a horse-drawn carriage.

Now, on the 200th anniversary of that journey, the places he visited are holding bicentennial events to commemorate the man and his legacy.

His April 28, 1825, visit to Carondelet and April 29, 1825, visit to St. Louis will be celebrated here on April 23-26 with a host of lectures, dinners, exhibits and an 1820s-style ball.

Michael Halbert, a historical interpreter, will appear in costume at the events in the person of Lafayette. Like all four of the interpreters who are playing the role of Lafayette in these celebrations across the eastern half of the United States, Halbert speaks fluent French and is well versed in the man and his times.

To celebrate the bicentennial of the Marquis de Lafayette’s 1824-1825 return to the United States, historic interpreter Michael Halbert portrays the statesman and general.

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, gained fame both in the fledgling United States and also his native France. A true believer in the Age of Enlightenment principles of freedom and equality, he came to this country when was just 19 to fight in the Revolution.

Commissioned in the Continental Army as a major general, he was wounded in the leg in his first action, the Battle of Brandywine. Gen. George Washington was so impressed by his heroism at that battle that he gave Lafayette command of a division.

The soldiers led by Lafayette from the north and a force of French soldiers commanded by the Comte de Rochambeau from the south trapped the British forces at Yorktown, Virginia. They sent word to Washington in New York, who moved his army to Yorktown to take the British army and win the war.

On July 31, 1777, during the Revolutionary War, the Marquis de Lafayette, a 19-year-old French nobleman, was made a major general in the American Continental Army.

“In the Battle of Yorktown, the last major battle in the war that gave us our independence, there were more French military personnel there than American,” Schwam says.

After the war, Lafayette headed back to France, where he continued to fight for human rights. With help from Thomas Jefferson, he wrote a draft of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, the French Revolution’s equivalent of the Declaration of Independence.

Among other things, that document states that all men are born free and equal, and that everyone has the right to liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression.

“But he also wanted the constitutional monarchy. Lafayette wanted to keep both sides happy, the people and the royals. And you know what happens when you try to keep both sides happy,” Schwam says.

He fled France, but was captured by Austrian soldiers and spent what Schwam calls “five dismal years in a terrible prison” in what is now Czechoslovakia. Napoleon, who by then had become emperor, arranged to have him freed, even though Lafayette did not support him.

Chuck Schwam, executive director of the American Friends of Lafayette, poses with interpreter Michael Halbert, who portrays Lafayette in events around the United States.

Lafayette then continued to fight for equality and human rights. He fought against slavery, which was not as polarizing an issue in France as it was here, Schwam says. And he made his views known on his famous trip to America.

“What I love about what Lafayette did is that he didn’t lecture us. He was very disappointed in what was going on in our country at the time, but he didn’t lecture us. He did things differently. He did things with action,” Schwam says.

“If he saw an African-American man he was friends with or served with him, if he saw him in the street he would hug him in front of all kinds of people. Nobody had really ever seen that before.”

Lafayette also spoke out for the rights of women. Women in France were not permitted to inherit any property from their husbands after they died, until Lafayette worked to get that law changed.

One result is that we have Veuve Clicquot champagne to this day, Schwam says. The iconic champagne house was run and expanded by a woman after the death of her husband, who had started it. “Veuve” means “widow.”

“He treated women as equals, to the point that they followed him around (this) country because they loved the fact that he thought they had the wherewithal to be able to do anything a man could do,” Schwam says.

A depiction of the Marquis de Lafayette, French-born hero of the American Revolution, being greeted at the home of Pierre Chouteau in St. Louis on April 29, 1825. He visited here during a 13-month tour of the United States. Artist John M. Heller of St. Louis painted this and other scenes from life in early St. Louis and presented them during the 1950s. Post-Dispatch file image

Lafayette’s 1824-1825 victory lap around the United States was a huge success. An estimated 4 million people throughout the country saw him, with balls held in his honor everywhere he went.

And his influence is still felt today, in some respects. Before he came back, only one city was named for him, Fayetteville, North Carolina. Today, nearly 80 towns bear his name in one form or another, along with innumerable other locations such as St. Louis’ Lafayette Park, Lafayette Square neighborhood and Lafayette Avenue.

The local celebration will begin April 23, with an all-day colloquium at Washington University about “Creole Culture in Upper Louisiana,” hosted by the school’s French Connexions Center of Excellence.

Beginning at 10 a.m. April 24, the French Heritage Corridor will hold its fifth annual conference, also at Washington University. Schwam will be on hand for this event to discuss the importance of Lafayette’s return to America.

The program includes lunch and a 5:30 p.m. cocktail reception at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum on the Washington University campus. Virtual attendance is also available through Zoom.

A sortir de classe (“get out of the classroom”) event will take place April 25 with a road trip to Ste. Genevieve to see French heritage sites, followed by a dinner at the St. Louis Mercantile Library.

The Chatillon-DeMenil House

The main part of the celebration takes place April 26, beginning at 9:30 a.m. with a re-creation of Lafayette’s visit to the home of Pierre Chouteau. Because that building is no longer standing, this event will take place at the Chatillon-DeMenil Mansion, 3352 DeMenil Place, which was the home of Pierre Chouteau’s granddaughter and Auguste Chouteau’s daughter.

A one-hour riverboat cruise commemorating Lafayette’s 1825 arrival in St. Louis will set off from the riverfront beginning at noon.

At 1 p.m. St. Louis will welcome Lafayette — or Halbert, the interpreter portraying him — at the Gateway Arch. That is the spot where crowds of St. Louisans came to greet him in 1825.

This event is free, and will include speeches from dignitaries and members of patriotic and historical societies.

The Lafayette Bicentennial Ball will be held from 6-10 p.m. at the Rose of the Hill, 2300 Edwards Street. Dinner will feature the same toasts made to honor Lafayette at a ball here in 1825, followed by period music and dancing led by a dance caller.

Attendees are asked to wear period costumes or cocktail or business attire.

Post-Dispatch photographers capture hundreds of images each week; here's a glimpse at the week of March 23, 2025. Video edited by Jenna Jones.