I met Jordan while he was tying a Naloxone kit to a park bench beside a small encampment in downtown Toronto. I was walking with my dog on the way to the park when he stopped me to ask for the time, despite him sporting two silver watches, one on either wrist. He was wearing blue, slightly torn Nitrile disposable gloves, so I assumed he was a social worker helping to distribute the fast-acting drug used to prevent opioid overdoses in areas of the city where people may need it most. I reached into my pocket for my phone and told him it was half past twelve. He thanked me and continued to casually tie the Naloxone kit to the park bench.

I was curious how he got a hold of those Naloxone kits, since I was denied one some years ago in one of the many pharmacies across Canada that distribute them freely. I was told that because I was not in close contact with anyone who had an opioid addiction, nor had an opioid addiction myself, it didn’t make sense for me to have one. Jordan, though, had been given the kits because he had an opioid addiction and had overdosed 18 times. With the opioid crisis waning, I learned that it was easier now than it was in 2021 to get a hold of Naloxone.

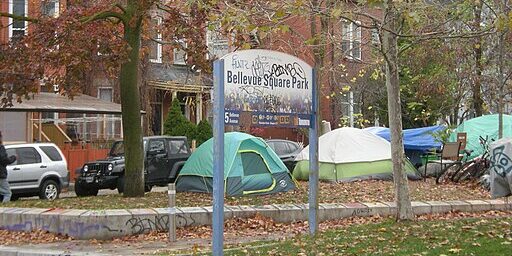

As perhaps expected, drugs and homelessness often go hand-in-hand. Jordan mentioned he is also unhoused, pointing to one of the two blue tents we were standing beside. He moved to Canada from Zimbabwe 23 years ago, and feeling like he had no guidance on how to find a job and a reasonably priced place to live, he resorted to robbery and selling drugs to get by. As the story goes, the drugs eventually got to him, too. Now he’s trying to help people who suffer a similar fate.

I asked if he had been to St. Mike’s Recovery Centre on Ossington and Queen St. in the west end of the city. He nodded as if to state the obvious, saying he’s been in and out of rehab without much success. Because of his addiction, Jordan has had a hard time finding a job, despite being on disability, having to face the undeniable cruelty of what comes with addiction and often subsequently, poverty. Whichever of the two comes first.

Without a clear segue, Jordan started going off on Drake. “And what the f— is that guy doing, man? He’s done nothing for this city. Why is he repping Atlanta?” I mentioned Kendrick Lamar’s “Not Like Us” diss track, and Jordan cracked a smile.

“Oh yeah, you heard that? Kendrick was right, he called him out on his s—.” Jordan was referring to Toronto’s very own rap artist making a killing from his albums while exploiting black culture, particularly the Atlanta rap scene, for his own monetary gains.

“He hasn’t done anything for his people here. Keeping all that money to himself. Just like all these politicians. Where do you think all our money goes?” I facetiously responded with taxes, but he maintained a deadpan stare and said, “Straight into their pockets.”

About a half hour passed, Jordan and I switching back and forth between politics, music, and everything in between. He eventually motioned towards the park bench where his Naloxone kit was tied as if to get back to business, but not before turning back to fist-bump me before we parted ways, he went back to his world, I back to mine.

Within the short time I spent talking to Jordan, there had been a number of issues he broached that many Canadians – not just Torontonians, are currently facing, ones that wreak havoc on our country’s socio-economic and political fabric. For one, Jordan’s unhoused status is a painful reminder of the thorn in our country’s side regarding unaffordable housing and lack of rent control. For instance, despite Doug Ford’s guideline rate, the average rent increased in Ontario by 55 per cent between 2014 and 2023, which was more than triple the guideline rate, highlighting a flawed system rigged with loopholes.

On top of unaffordable housing, inflation, low salaries and a lower minimum wage are of no match to the high cost of rent, let alone a home purchase. Moreover, the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) released a devastating 2025 study that recorded upwards of 80,000 Ontarians as homeless in 2024, a 25 per cent increase since 2022. This number is expected to double in the next 10 years, reaching almost 300,000 without meaningful intervention by the province.

Jordan’s unemployed status also reminded me of Ford’s comments late last year about healthy Ontarians needing to “get off their a-s-s-e-s and start working like everyone else.” What about unhealthy Ontarians? The Internet erupted with opinions oscillating between Ford imitating tone-deaf delirium while ignoring the reality of the labour market, to blaming unemployment levels on immigration and more specifically, temporary foreign workers and international students.

To be clear, both the housing crisis and the diminishing job market were problems festering long before Canada initiated a near open-door policy for immigration, reaching as far back as the end of the Second World War. To blame immigration for the housing crisis and unemployment is to ignore the government’s mishandling of inflation, fewer investments in housing despite a growing population, and the exploitation of temporary foreign workers for cheap labour as an attempt to boost the economy.

Jordan also talked about immigrating to Canada and the accompanying disorientation and alienation he experienced within the system. Canada was at one point a pioneer in immigration policy, with Trudeau’s 2023-2025 Immigration Levels Plan promising to welcome 465,000 permanent residents in 2023, 485,000 in 2024, and 500,000 in 2025. But the pedestal that our country once proudly stood upon is wobbling. Today, the backlog of applications and the stresses of unemployment and underemployment have caused Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), the Canadian government department that handles immigration issues, to pause its intake in December 2024, reducing 64,200 applications to streamline its process. Canada also plans to reduce targets for permanent residency from 500,000 to 395,000 in 2025.

And finally, the ubiquitous wealth inequality was blaringly obvious from Jordan’s Drake comment. According to a 2023 Oxfam Canada report, the world’s richest one per cent brought in two-thirds of new money since 2020, reaching a staggering $42 trillion and doubling that of the bottom 99 per cent. Political campaign slogans like ‘Tax the rich’ to curb extreme wealth inequality and concentration are heard habitually. In her address to the United Nations 2024 ECOSOC Special Meeting on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, Erica Payne, founder and president of Patriotic Millionaires, called on world leaders to increase taxes on the rich to wrestle extreme wealth inequality. Noble stories of the uber wealthy sharing their piece of the pie by donating to non-profits were being praised, like when MacKenzie Scott donated $16.5 billion from the fortune she received from her divorce from her very rich and very famous ex, Jeff Bezos (see Amazon).

The Canadian dream, if there ever was one, has become a real nightmare. Jordan, like many of us, reap the unfortunate consequences from a system that has historically failed to resolve such issues, despite promoting efforts to. For example, supervised consumption sites across the country had reversed 16,000 overdoses between March 2020 and January 2024 with the same Naloxone kits that Jordan was distributing in the park. But this effort was rescinded when Health Minister Sylvia Jones announced in July 2024 that the provincial government will close 10 supervised consumption sites for March 31, 2025, and prohibit new sites from opening, despite concerns from health workers and advocates raising the alarm of a potential increase in deaths from overdoses.

We have seen attempts to mitigate the widening inequality gap with Ontario’s pilot program for universal basic income between 2017 and 2019, offering low-income households (under $34,000 per year for single occupants or under $48,000 per year for couples). But the program was cancelled when Doug Ford became the new premier, despite 83 per cent of recipients reporting lower levels of mental stress, increased financial wellbeing and housing security, according to a report by Carlton University’s School of Social Work and the Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction. Adding more salt to the wound, The Conference Board of Canada’s recent economic report card graded Canada a D, ranking 11th out of 16 countries evaluated.

And when we look at our current immigration system, there has been a lack of cohesive communication and preparation between the federal and provincial governments. The former selling an alluring yet false reality to newcomers while not understanding labour market demands on the provincial and municipal levels nor the employers’ perspectives. Previous prime minister Justin Trudeau put a cap on temporary foreign workers and limited them to one-year contracts due to widespread unemployment. Even newcomers are leaving the country after failing to land a job in Canada.

There have been some positive strides towards resolution, however. Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow announced at a press conference on October 2, 2024, that a Canada-Ontario rent supplement plan to help families living in shelters move out was set to resume this past fall. AMO stated that this came at a time where municipalities wrestled with the balance of treating the unsheltered with respect and empathy while ensuring the surrounding communities feel safe and protected in the public sphere.

As of January 30, 2025, the City of Toronto released a budget proposal to secure hundreds of millions of funding with the Federal Interim Housing Assistance Program (IHAP) to offer shelter to refugees. The city also secured increases to the Canada-Ontario Housing Benefit, a supplemental rent offer that encourages people living in shelters to find a home, which subsequently offers up space to bring in people from encampments. And there’s more: the AMO states an additional $11 billion will be used to end homelessness within the next decade by providing affordable housing and promoting prevention programs.

Canada’s Homelessness Strategy, along with the National Housing Strategy, which plans to invest more than $115 billion over a 10-year period to build homes for Canadians sounds promising, but time will tell to see if this plan will fall through the cracks of a policy graveyard or not.

Community-based approaches present alternatives to address failed provincial policies. The United Way’s Inclusive Local Economic Opportunity (ILEO) initiative, for example, focuses on community-based advocacy and innovation towards issues that impact underserved neighbourhoods in greater Toronto. The initiative is set out to bring together systems change among private, public and community sectors through innovative ways to increase economic equity on the local level, particularly newcomers, racialized individuals and lower-income households – with business opportunities and better employment. In essence, what is put into the community, goes directly back to them.

While it may be easy and perhaps convenient for society to blame the individual for not shouldering most of the responsibility for their own actions, the surrounding community is equally, if not more accountable for addressing the conditions that prevent healthy progress. If we are to come close to any sort of headway, contributing systemic factors that manifest such conditions – often economic factors, family structures and socio-cultural environments – must be scrutinized and re-evaluated to create more effective and meaningful policies. If failed governmental policies can’t help us, then maybe we can help each other instead through the community. And when all is said and done, no one will come to save us but ourselves. Although Jordan comes pretty close.

Prior to joining United Way Greater Toronto, Lisa had begun writing this article in August 2023. She completed the article in March 2025 after learning about United Way’s Inclusive Local Economic Opportunity (ILEO) project. She is now an Associate Manager, Strategic Initiatives for ILEO.