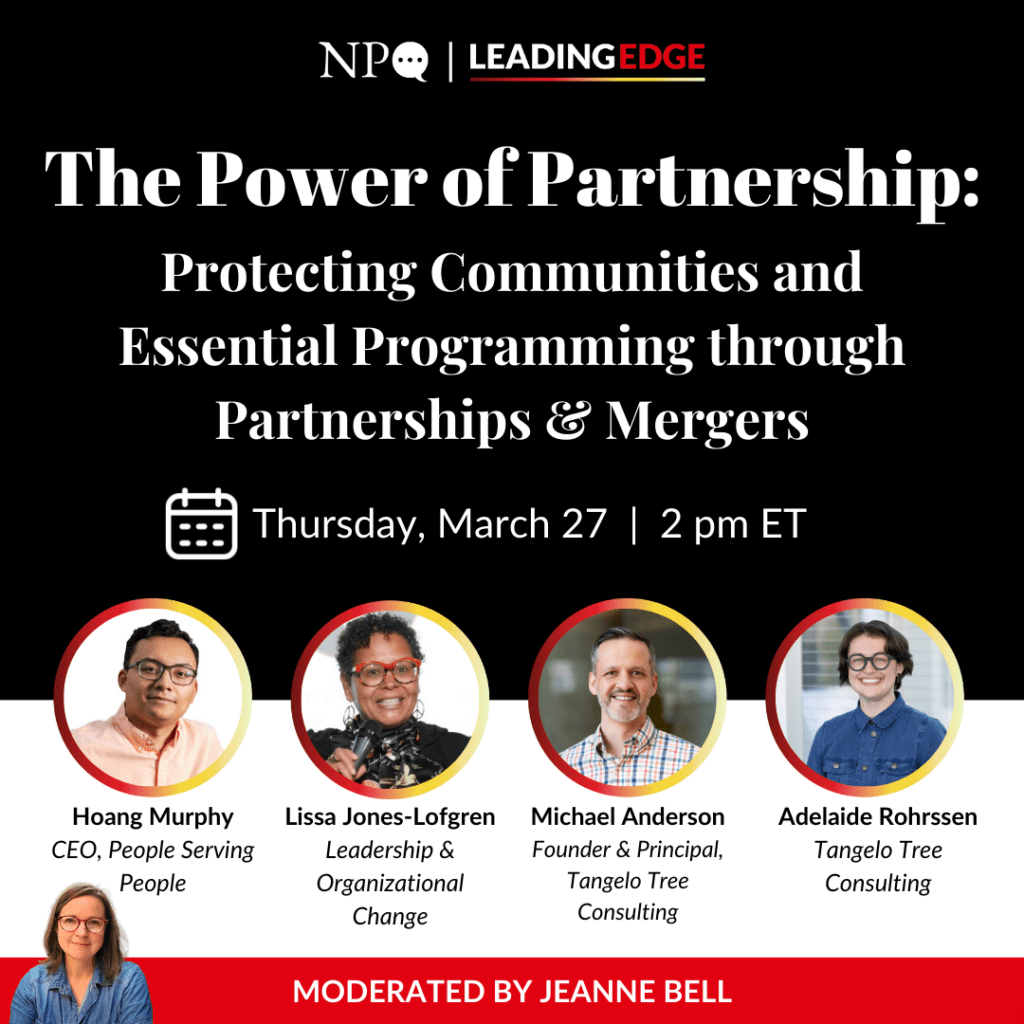

It’s a rite of passage in spring, when hotels overflow, attendees with nametags on lanyards flood the streets, and alcohol sales at hotel bars smash records. It’s AWP: The Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) annual conference for the nonprofit of the same name, which serves creative writers, academics, publishers, and literary journal and book editors.

Self-described as “the largest annual gathering of writers in North America,” AWP includes panels on the craft of writing, pedagogy, publishing, and literature. There are readings, both on-site at official conference hotels and off-site at any number of bars and bookstores. And there’s a massive book fair, where writers sign books, overstuff their tote bags with yet more books and magazines, and connect with editors.

AWP has attracted a fair amount of criticism over the years, ranging from economic injustice—conference registration alone costs up to $540 and registration is strictly enforced; the conference is held in expensive cities, usually on the coasts—to its emphasis on writers in the academy, specifically tenured professors, to the neglect of non-academic writers and those who do adjunct labor. It’s also been criticized for lack of diversity in its panels and programs and ableism—from not having accessible stages or wheelchair-safe floors to not enforcing its own mask policy to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

To hold a conference in a city recently devastated by disaster is to come face to face with the climate crisis—and acknowledge the crisis has many layers.

This year, some of the criticism AWP faces is site-specific. It is being held in Los Angeles, CA, mere months after climate change-accelerated wildfires burned over 37,000 acres, destroying more than 16,000 structures, killing at least 29 people and displacing thousands. While AWP is huge (about 12,000 people attend on average), it is far from the only conference scheduled to touch down in an area still reeling from a climate event.

Your Dollars Are Needed

The argument for continuing on with a conference in a climate impacted area is the same one for going ahead with any kind of tourism following disaster: Travelers mean money.

Cities and the hotels and conference centers in them count on the dollars from big events, which are often scheduled many months if not years in advance. Along with lodging, conference attendees spend money on food, transportation, entertainment, and souvenirs. The last time I attended AWP, in 2019, a rideshare driver told me his entire weekend of fares had been from writers.

“I won’t be attending AWP this year because the local community is already overburdened with trying to rebuild after the climate disaster.”

The economic boost of a conference has a trickle-down effect, especially for small businesses near a conference center. And the absence of sales after a disaster hits these smaller businesses hard.

“Almost all tourists disappeared,” Jenna Spencer, co-owner with her husband of the Last Bookstore, an independent book and record shop, told The Washington Post for an article, “Los Angeles Wants You Back.”

Spencer related that in January, the month of the Palisades and Eaton fires, foot traffic to her store dropped by 80 percent. By the end of February, business was still down 20 percent. Two weeks after the fires, cancelations at one Santa Monica hotel, which later offered refuge to those displaced by the disaster, amounted to almost $700,000 in lost business.

Even restaurants, which The Washington Post described as “not typically tourist-dependent,” are facing huge losses as people don’t have the funds to go out to eat or who have left the LA area entirely. Those deficits are expected to be ongoing. “It’s hard, if not impossible, to quantify the damages we will incur in the next few years,” restaurant owner Francesco Zimone told the Post.

Many conferences and events set to be held in the city soon after the fires, like the insurance industry conference INTRConnect 2025, were canceled or postponed, but the 2025 Innovations and Solutions for Ending Unsheltered Homelessness Conference went on as planned in LA, and organizers of the Grammys were clear about holding the award show as planned on February 2 as a way to support the city. The Center for Effective Philanthropy (CEP) conference is scheduled for the area later this year.

Elsewhere, the nonprofit Appalachian Studies Association (ASA) held its conference in Cookeville, TN in late March—and in September, Funding for Good’s Nonprofit Consulting Conference will be held in Asheville, NC, a year to the month after deadly, destructive flooding.

A Balancing Act

It was late September of 2024 when Hurricane Helene caused a massive storm surge thousands of miles inland, impacting Asheville and other parts of North Carolina and Tennessee. The storm caused roughly $250 billion in damages. In North Carolina alone, nearly 100 people died. Asheville was without safe, drinkable water for months. The city, already somewhat difficult to access due to its remote and mountainous location, dealt with rural roads washed away, broken pipes, flooded water treatment plants, downed trees and powerlines, and no electricity.

The month after the hurricane, Asheville officials and residents in the popular tourist destination made a public plea for visitors to stay away. “We are asking people to support from a distance (for now),” Mickey Poandl, public relations manager for the city’s tourism bureau, Explore Asheville, told Forbes, which described the area as being caught in “a balancing act between physical and economic recovery.”

Some people are still living in those hotels, emergency lodging meant to be temporary now stretching out for months.

Resources were needed for recovery efforts, which could be complicated by extra people on the ground. Those resources included scarce water, food, and lodging. Restaurants couldn’t open due to the lack of water. Large amounts of debris made the area hazardous to traverse. Already limited roads did not need to be crowded with extra vehicles.

And with over 100,000 homes heavily damaged or destroyed in western North Carolina, hundreds of thousands of residents were without a safe place to stay. Some sought refuge in shelters, including temporary shelters like a gym. Those quickly reached capacity, and local hotels—once they had running water—opened their doors to climate survivors. As home repairs are delayed and insurance claims are denied or postponed, some people are still living in those hotels, emergency lodging meant to be temporary now stretching out for months.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

That’s an issue in LA, where local hotels and short-term rentals took in residents impacted by the wildfires. With around 150,000 LA residents displaced, many are still in hotels, three months after the fires. As NBC News reported, even “survivors whose homes are standing face ballooning smoke remediation and restoration costs, as well as insurance companies that are lowballing payouts.”

According to NBC News, survivors “anticipate being displaced for months as they begin rebuilding.”

Concerns about LA residents are on the minds of some writers who purposefully opted not to attend the LA-based AWP conference.

Writer Sarah Fawn Montgomery told me, “I won’t be attending AWP this year because the local community is already overburdened with trying to rebuild after the climate disaster, and the money I would spend to attend can be better used to support organizations that will assist with that necessary work.”

Others questioned the wisdom of planning a large conference in an area shortly before what is typically its wildfire season—although thanks to climate change, wildfires are occurring chaotically at other times and at much greater intensities. One California-based writer, in a private correspondence, mentioned they had proposed a panel on wildfires, but it was rejected.

How to Convene Respectfully

As more and more places globally are impacted by climate disaster—often, repeatedly—they’re becoming difficult to avoid, let alone predict. How can nonprofits and other groups host events that contribute to local economies while still being respectful and supportive of recovering communities?

It’s a matter of timing. Just two weeks after Explore Asheville made a public plea for tourists not to come, the Asheville tourism office pleaded for vacationers to return, which didn’t sit right with many residents. When an area is still actively reeling from a recent climate event, your group should not take resources away from struggling residents, clog roads or hotels, or interfere with emergency efforts. Wait until community members welcome the public back.

Avoid specific disaster zones. “It’s ethical and imperative for travelers to visit Los Angeles now,” Dominica Deluca, owner of skate shop Brooklyn Projects in Hollywood, told Condé Nast Traveler. “It helps the city.” But Condé Nast Traveler stressed that visitors need to avoid any nonessential travel to the hardest hit areas in LA including Altadena, Malibu, Pacific Palisades, and Ventura. It’s unsafe and it’s disrespectful. Don’t be a disaster tourist.

Give back. To simply be in a disaster-impacted city and spend tourism dollars isn’t enough for a large group, which has the capacity to do more (and which, by its very presence, is a source of additional pollution and waste). “Major conventions that have hosted meetings in Los Angeles since the wildfires began have also prioritized giving back,” according to LA Tourism and Convention Board president and CEO Adam Burke.

That’s a stated priority for AWP, which normally is a money-making event for the nonprofit. This year the conference is instead kicking off with a Benefit for LA Fire Recovery, hosted by actor and writer Amber Tamblyn, and sponsored by Live Talks Los Angeles.

Acknowledge the crisis. With 2,000 presenters and 550 events at AWP in LA, only 15 mention “climate” at all in their title or event description. To hold a conference in a city recently devastated by disaster is to come face to face with the climate crisis—and acknowledge the crisis has many layers.

Some of the areas hardest hit by the LA wildfires were predominately Black neighborhoods. Some of the people most vulnerable to long-term health problems from the fires, like lung issues from air pollution, are disabled. This is especially hard when most large conferences, including AWP, no longer require masks, proof of vaccinations, or take other health safety measures.

For Montgomery, it’s an issue not only of climate and economic justice, but disability justice. “As a disabled person, I’m also acutely aware that climate change is a disability rights issue, disproportionately impacting disabled people who are more susceptible to being impacted by severe weather and less likely to be able to continue treatment, seek emergency medical care, or even flee to safety.”

“Given how many conferences have returned to pre-pandemic policies around health and safety, this choice [to not attend] was easy.”

For More on This Topic:

What Can a COVID Outbreak at a Writing Conference Teach Us about Community Care?

How Do Political Conventions Contribute to the Climate Crisis?

Gender Inequality Needs a Platform at Climate Talks