Conversations around the representation of South Asian artists within British art history have bottlenecked in recent years. These frequently stilted debates are the result of tensions between three aspects: the significant presence of South Asian artists in Britain for more than a century; different perspectives on how to discuss this within the canon of British art history; and a perception of limited institutional recognition for South Asian artists working, living or born in Britain.

Is it even possible to give a concise overview of the experience of South Asian artists within the context of British art history?

This article does not seek to resolve these complexities but highlight key touchstones and connections. By focusing on one artist from each decade since the 1920s, the piece examines narratives of nationalism, empire, migration, religion and postcolonialism, which may continue or disrupt traditional narratives in British art history. Yet perhaps trying to impose a coherent narrative on such a diverse and expansive collective experience is itself an impossible task.

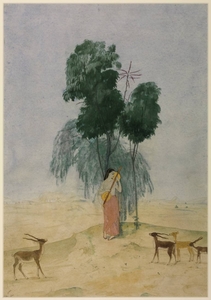

1920s – Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin

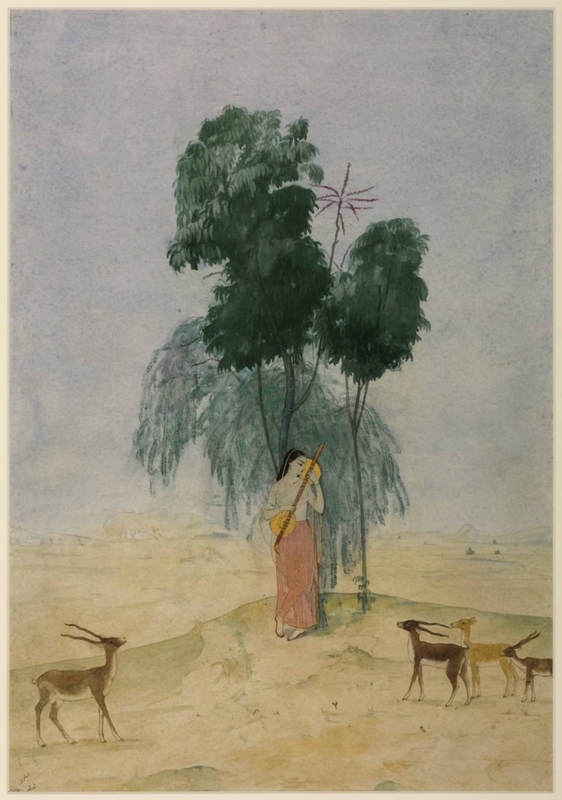

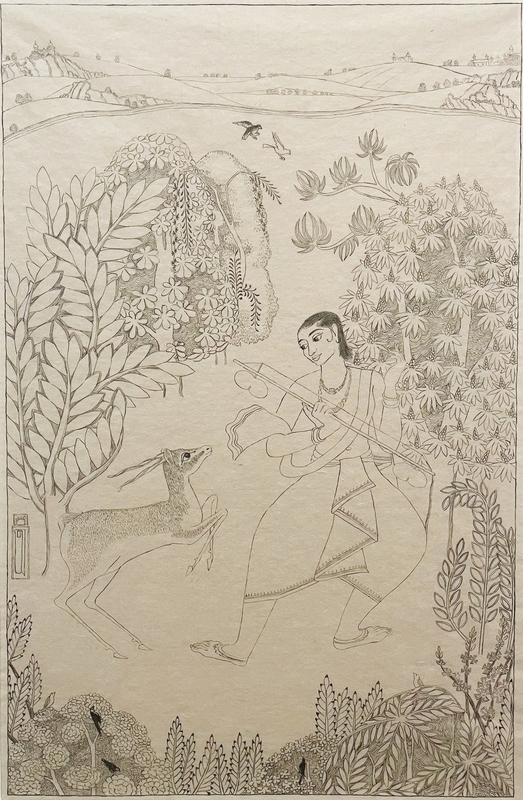

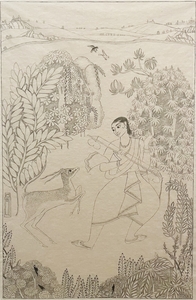

Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin is a pivotal figure in the history of modern art in Britain, though his significance has only recently been recognised. Born Samuel R. Samuel in Poona (now Pune) into a Jewish community in 1880, he first arrived in Britain in his early twenties to study at the Royal Academy of Arts. His most impactful artistic period began after 1912, when he married Atiya Fyzee, converted to Islam, and adopted the name Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin.

During this phase, he abandoned Edwardian portraiture in oil, instead developing a style inspired by Mughal era Rajput painting. Although he returned to India in 1908, his work was exhibited internationally, and in 1925, Raagni Todi Goddess Tune entered the Tate's collection, potentially making Fyzee-Rahamin the first person of colour represented in Britain's national collection of modern art.

Fyzee-Rahamin's presence in public collections in Britain – his work is also in the Manchester Art Gallery – upends narratives of 'diversity' and 'representation' in British art history. This is often framed as a linear narrative, with post-war and post-Empire migration – the results of which were an increasingly multicultural society – correlating to more diverse artists representing British art. You can read more about the artist in this story.

1930s – Abani Roy

Abani Roy, born in Bengal in 1904, was deeply engaged with Britain's interwar art scene. Enrolling at the Royal Academy in the 1920s, he left before completing his studies but built a significant artistic presence in London. Roy's close relationship with Jim Ede – the influential curator and founder of Kettle's Yard in Cambridge – demonstrates his integration into British art circles.

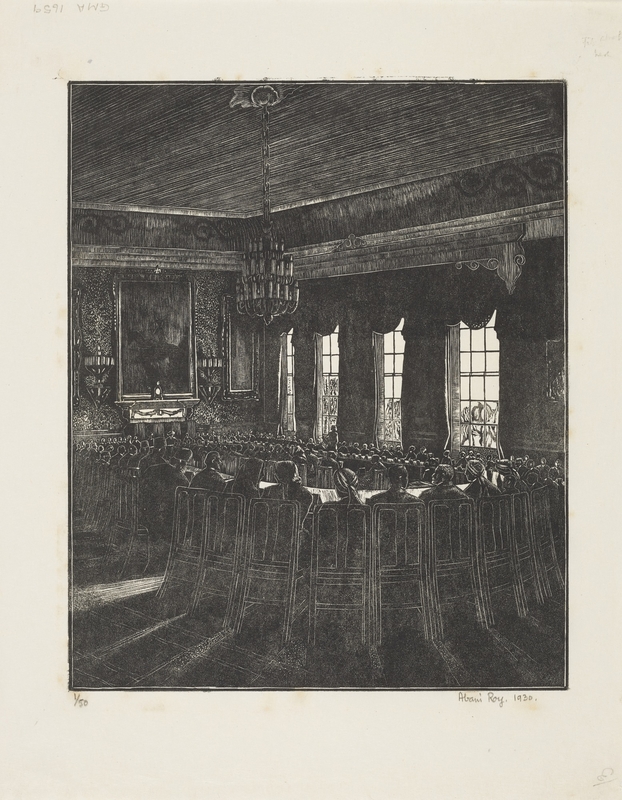

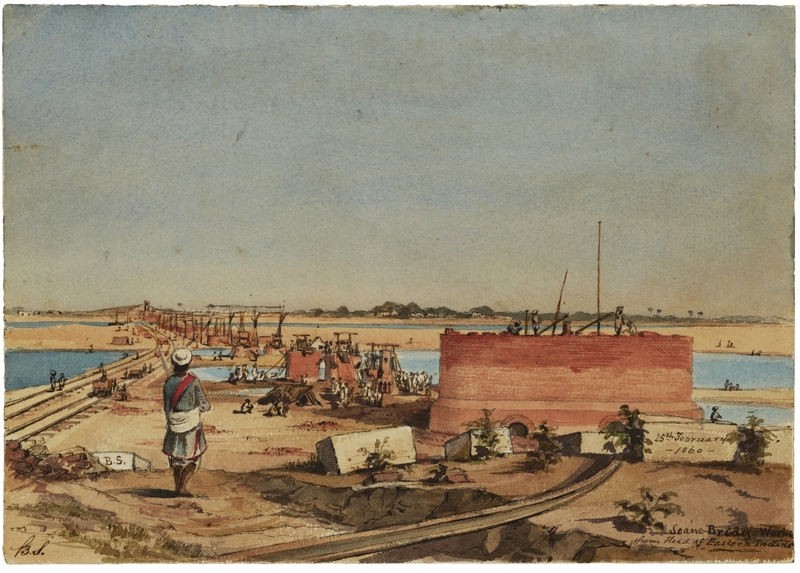

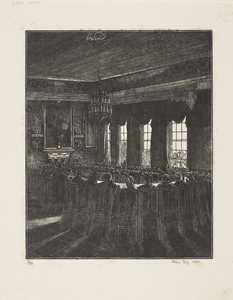

In an engraving from 1930 titled Indian Round Table Conference, Roy depicts a scene from the first of three conferences that took place in London between 1930 and 1932, convened by the British Government and featuring representatives from Indian parties, with the goal to address constitutional concerns.

Here Roy positions himself as a documentary artist, presiding over the elite chambers of dialogue between those representing British rule over India and Independence movements, as well as the processes that work towards constitutional codification. Roy's print is a visual depiction of the geographical bureaucracy that resulted from British rule in India being weighted in Westminster. As an artist from India based in London at the time, Roy's work is symbolic in the way it complicates the gaze of colonial representation.

1940s – Anna Molka Ahmed

Fyzee-Rahamin and Roy represent South Asian artists who were active and engaged within British art circles in the interwar period during the final burn of the British Raj. Yet the focus is often on artists migrating to Britain from postcolonial nations. Anna Molka Ahmed subverts this dominant narrative in terms of migratory movement: she in fact left Britain and settled in Pakistan.

Born Molly Bridger to Jewish parents in London in 1917, she went on to study at St Martins and the Royal Academy, while also converting to Islam in her adult years. She moved to Lahore in 1940, and after Partition become a significant figure in the cultural institutionalisation of the new nation of Pakistan. She set up the Department of Fine Art at the University of the Punjab and established herself as a painter through vivid landscapes and allegorical themes underscored by an Islamic socialism.

In 2006, Pakistan Post issued stamps memorialising ten nationally significant painters, including Molka Ahmed.

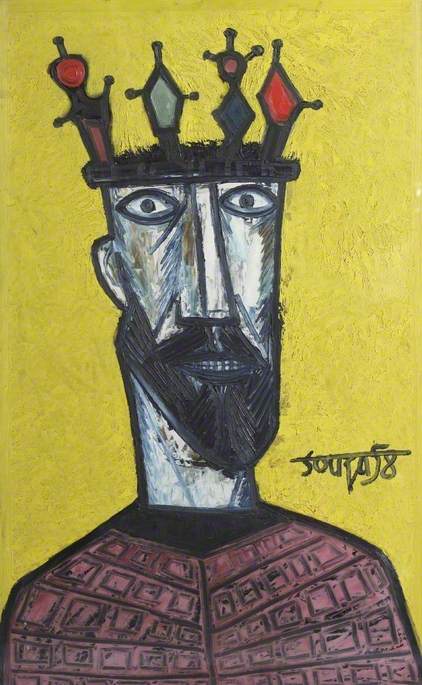

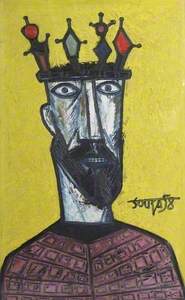

1950s – F. N. Souza

The 1950s marked the post-independence and post-Partition relationship between Britain and South Asia. Artists such as F. N. Souza worked to make sense of this while creatively and physically travelling between Britain and a now independent India and Pakistan.

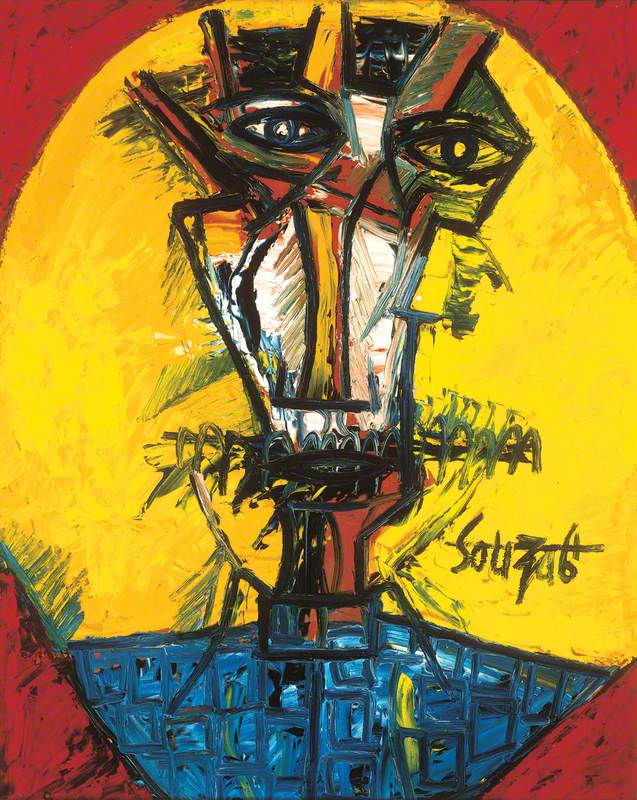

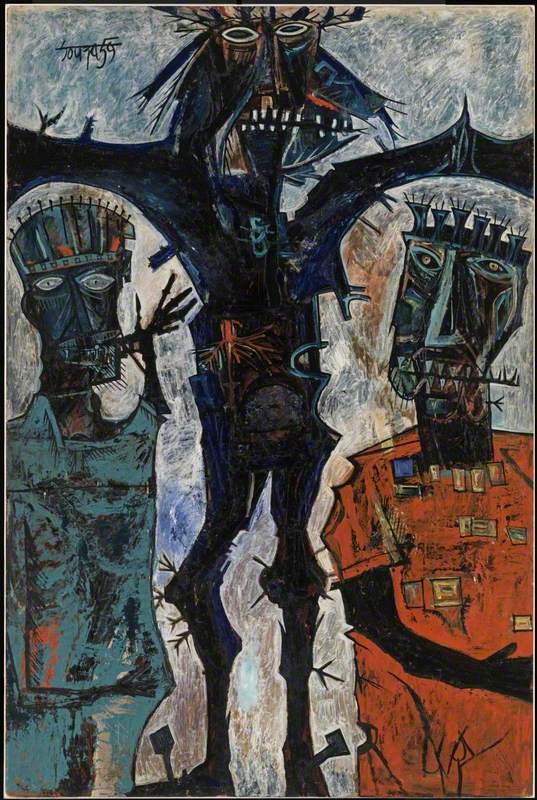

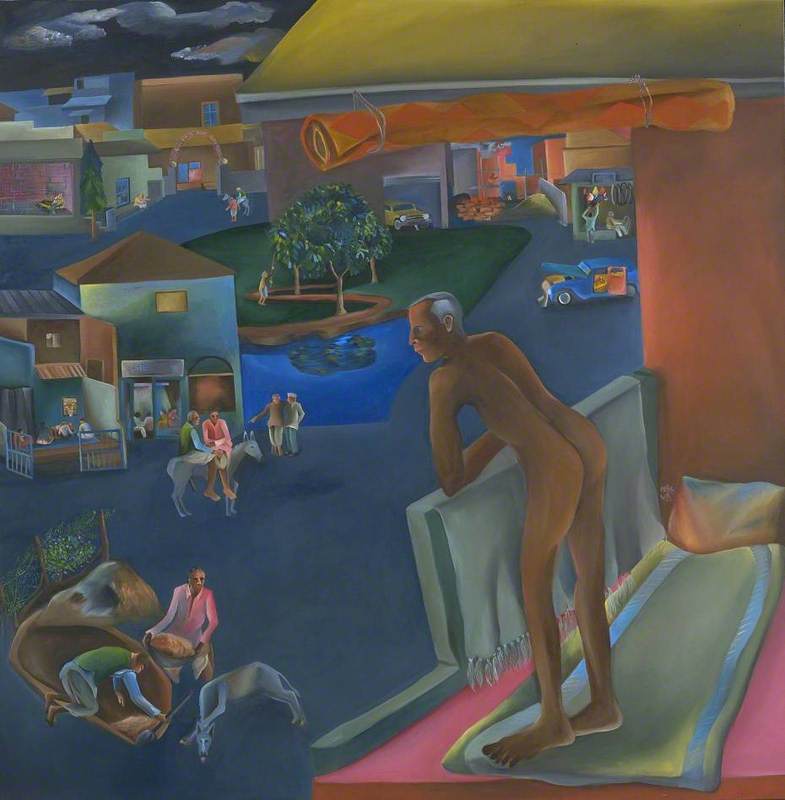

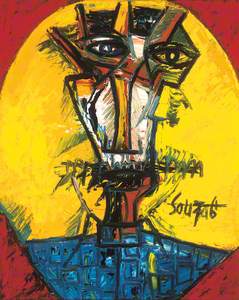

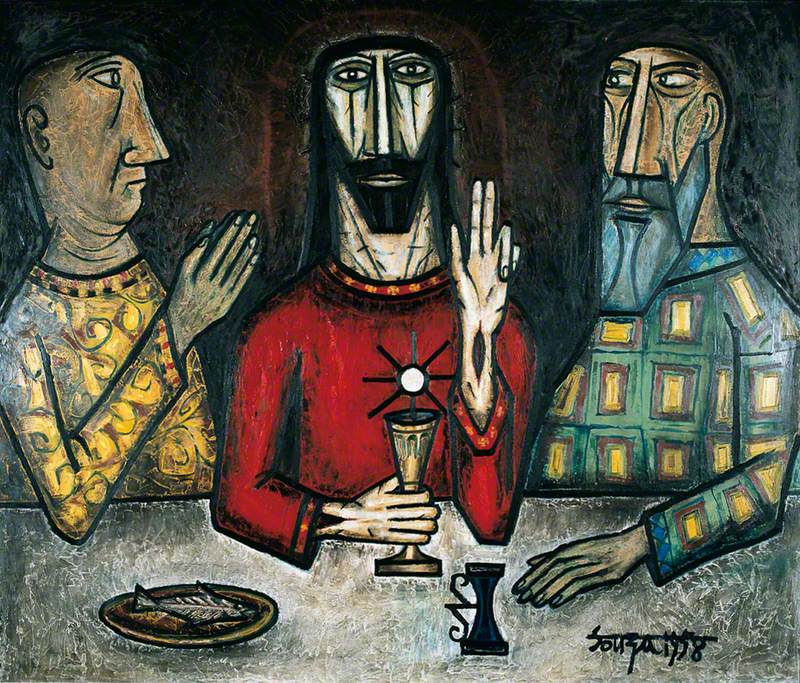

Born in Goa in 1924, Souza co-founded the Bombay Progressive Artists' Group in 1947, aiming to redefine modern art in a postcolonial context. In 1949, he moved to London, where his expressionist style – characterised by distorted forms, vivid textures, and provocative religious and erotic themes – captivated and unsettled audiences.

© Estate of F N Souza. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: The Hepworth Wakefield

Supper at Emmaus with the Believer and the Sceptic 1958

Francis Newton Souza (1924–2002)

The Hepworth WakefieldHis works, such as Crucifixion (1959), reimagined Western religious iconography through a postcolonial lens, drawing on the relational complexities between colonialism and Catholicism.

Souza's bold artistic statements, forged in mid-century Britain, resonated with a society grappling with the end of Empire and the beginning of the drift to a multicultural identity.

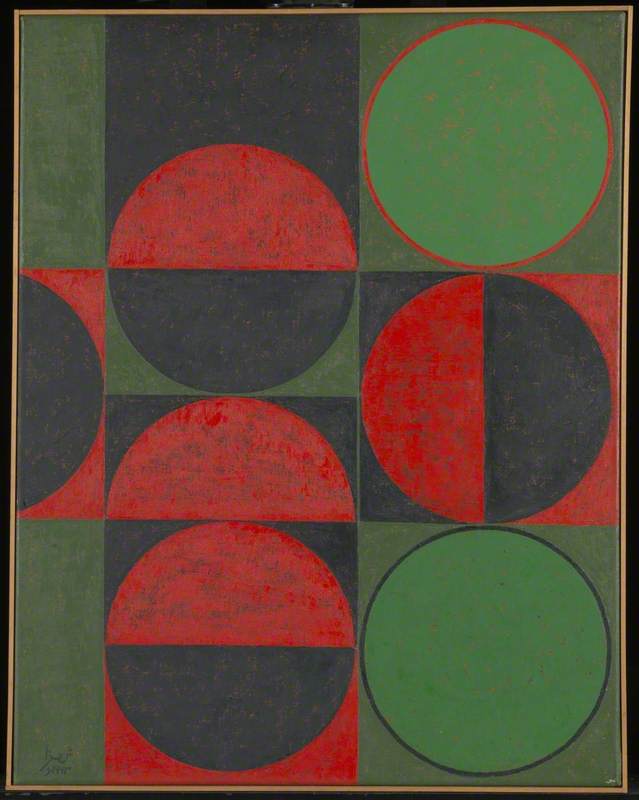

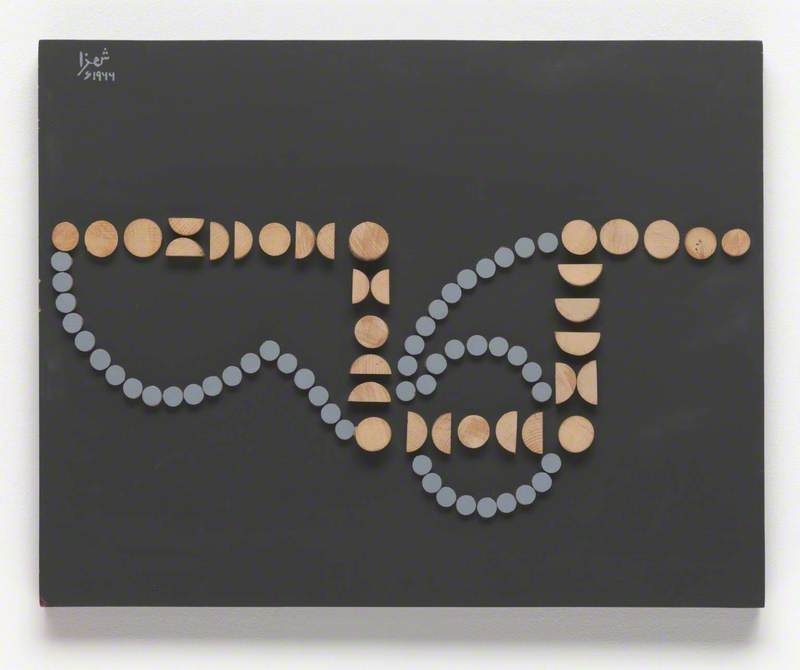

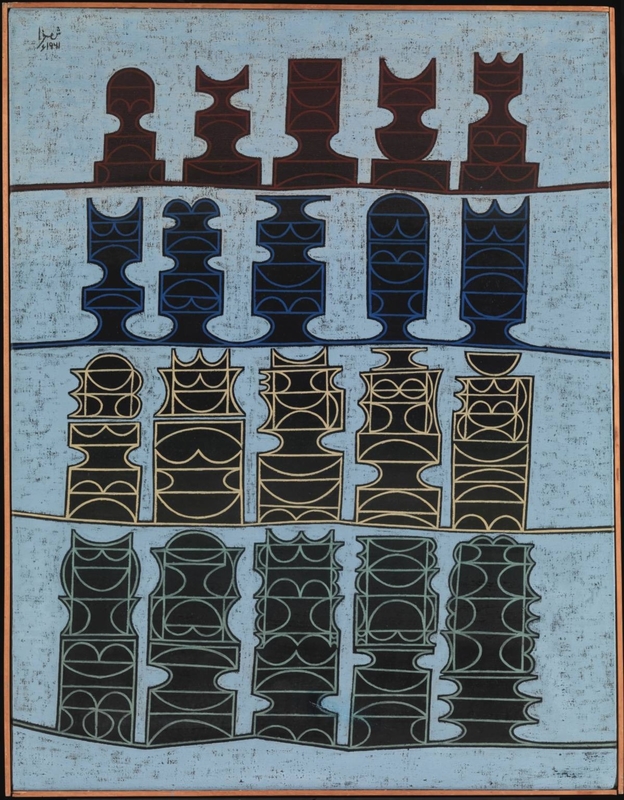

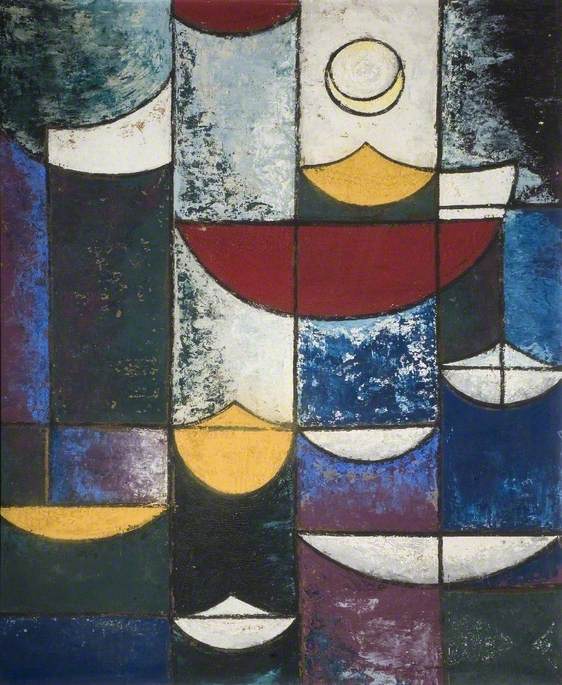

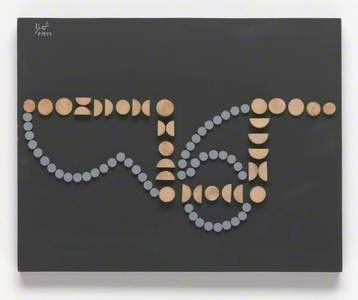

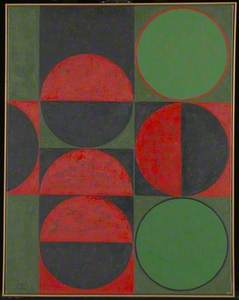

1960s – Anwar Jalal Shemza

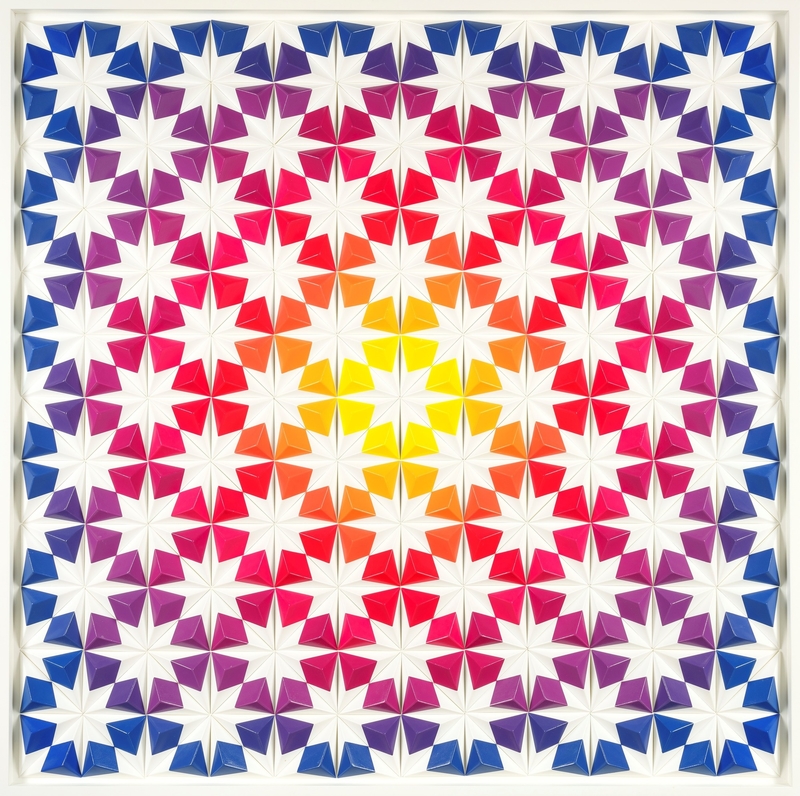

Born in Simla (now Shimla, India) in 1928, Anwar Jalal Shemza studied at Lahore's Mayo School of Arts and established himself as a writer and an artist. He came to Britain in 1956 and studied further at the Slade School of Fine Art where he was frustrated at how art history was taught: lecturer Ernst Gombrich's dismissal of Islamic art as purely functional had a profound impact and led him to abandon all his previous work in search of a different style, going on to consider modernism via both Western and Islamic art.

Alongside an examination of abstraction through geometry, calligraphy and spatial relationships, Shemza's work – which is now well represented in British public collections – deliberately incorporated references to Islamic traditions (script, tradition, belief).

Working as an art teacher in Britain until his death in 1985, Shemza continuously innovated. Yet despite being prolific in his lifetime, his legacy has been retrospective – it has only been since the 2000s that he has gained recognition for his place within both British and international modernism.

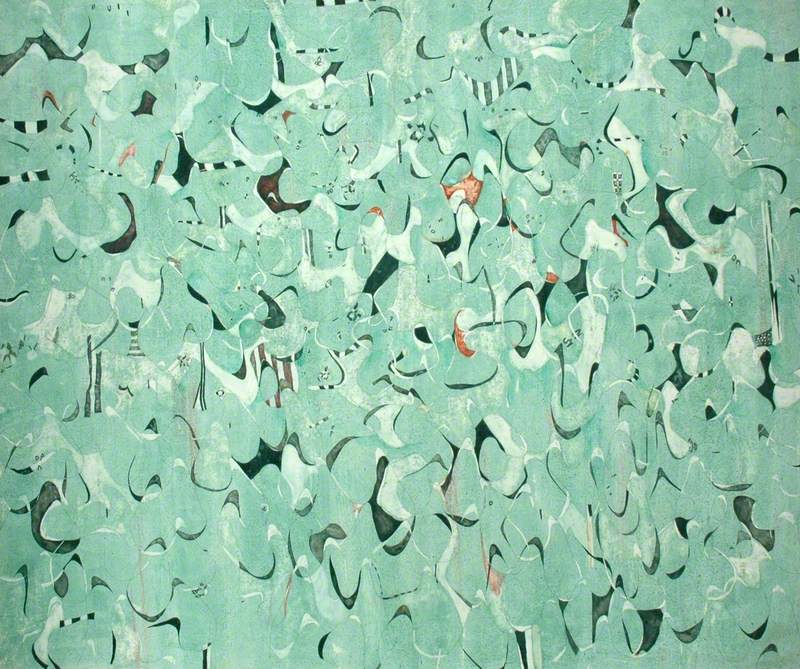

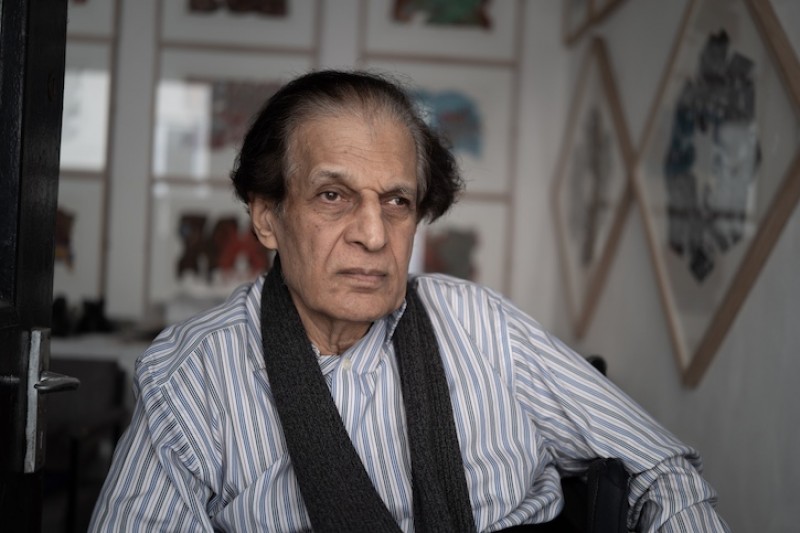

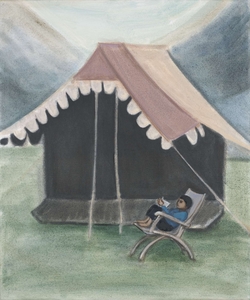

1970s – Prafulla Mohanti

Born in Nanpur, Odisha, in 1936, Prafulla Mohanti arrived in London in 1959 after studying architecture in Bombay. However, he quickly encountered systemic barriers, with British architectural firms often refusing to recognise his qualifications. Enrolling in a town planning course in Leeds, he began exhibiting his art alongside studying.

Mohanti's work is characterised by vibrant explorations of colour, abstraction, and the circular form – symbolic of the trio of Hindu gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva.

Across seven decades in Britain, Mohanti's artistic practice has included literary works, performances, documentary films and numerous exhibitions.

Mohanti continues to pursue the Indian philosophical concept of Shunya – translated as a silence or nothingness – capturing this profound concept through his art and philosophy. His enduring contributions show the spiritual interjections of different faith traditions from South Asia being centred within British art history, but whether there has been the appropriate lens to view and value these traditions remains to be seen.

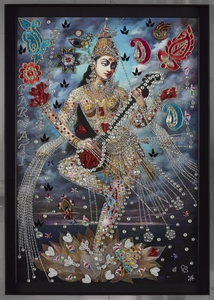

1980s – Chila Kumari Singh Burman

Chila Kumari Singh Burman's 2020 Winter Commission at Tate Britain brought joy during the pandemic through the constellations of neon light figures and forms, texts and trinkets installed across the façade of Tate Britain's neoclassical building.

View this post on Instagram

It was the colourful expression of a practice that emerged in the 1980s and which continues to flourish. Burman's most recent exhibition 'Spectacular Diversions' at Compton Verney also featureed a neon display on the façade of the museum building.

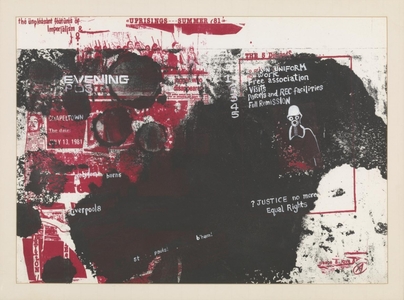

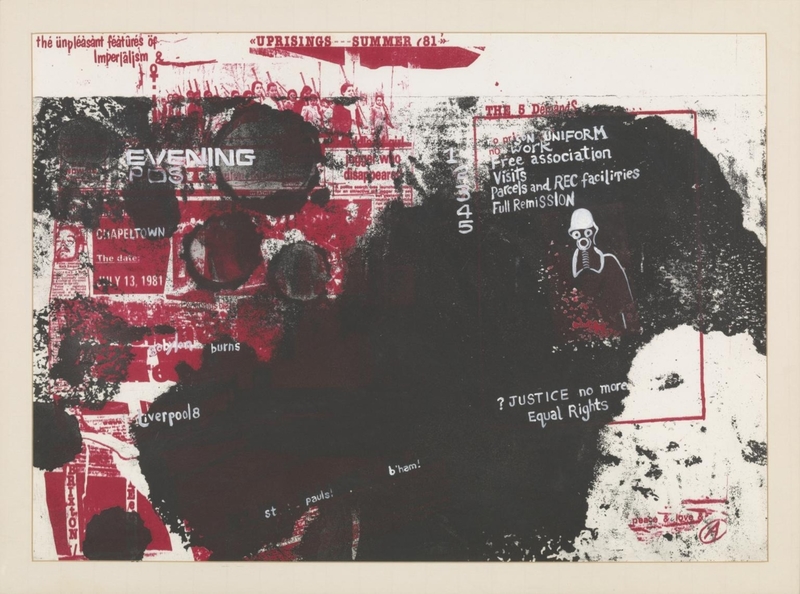

Born in Bootle to Punjabi parents, Burman's work has consistently engaged with activism, individuality and memory via a punk aesthetic that is seen through a diasporic, Punjabi, Liverpudlian feminist lens.

© Chila Kumari Singh Burman. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: Tate

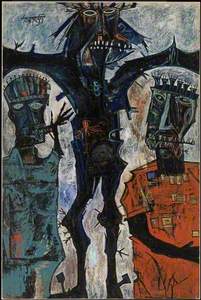

If There is No Struggle, There is No Progress - Uprisings (Riot Series) 1981

Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957)

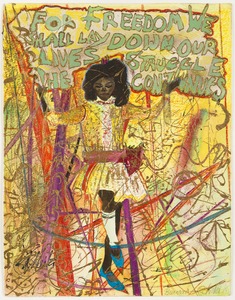

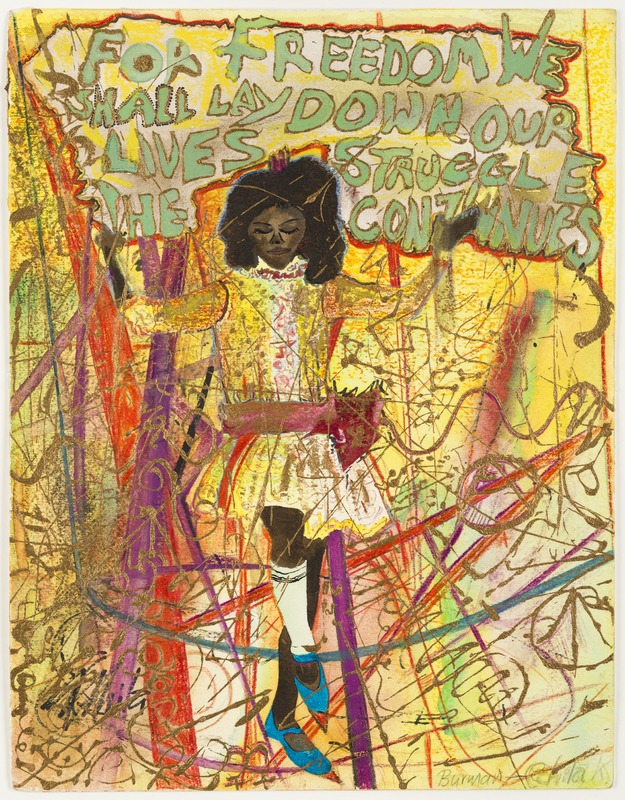

TateThis is exemplified by her early work, such as For Freedom We Will Lay Down Our Lives, which boldly centres how artists of South Asian heritage were crucial to the British Black arts movement of the 1980s. You can read an interview with the artist in this story.

© Chila Kumari Singh Burman. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

For Freedom We Will Lay Down Our Lives 1984

Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957)

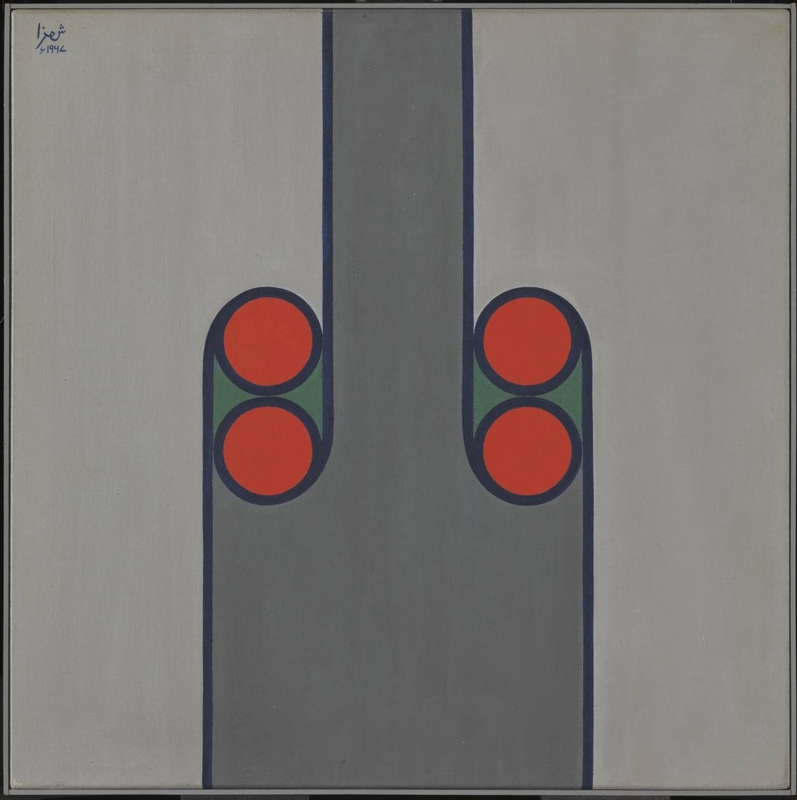

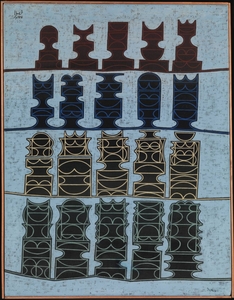

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage1990s – Hammad Butt

There are four significant installation pieces that Hammad Butt left in an infinite legacy. Installation is how these works, such as Familiars (1992), are now often described, although Butt disliked the term – for him, they were sculptures. They were explorations around the concept of sculpture itself, often described and framed through notes, essays and formulas drawing on the language of science and art.

Born in Lahore, Butt was raised in London, going on to study at Goldsmiths and making a series of significant works in the 1990s before passing away from AIDS in 1994, aged only 32. Despite his work being in public collections and him having a presence in the British art world of the '90s, Butt's contribution is only now being reappraised.

'Apprehensions', a retrospective of Butt's work, is currently on show at IMMA, Dublin, and will tour to the Whitechapel Gallery in June. It positions his practice and legacy as 'a pioneer of intermedia art, sculptural installation, sci-art and queer diasporic art'.

Butt's work Transmission (1990), which was part of his degree show, is symbolic of the scientific yet sacred chambers his sculptural formulae explore.

An electric cable connects a circle of glass books lit by ultraviolet. Each book rests on a metal rihal, evoking a Qur'an stand, and shows a single Triffid from the cover of John Wyndham's 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids. As with all Butt's works, there is a site-specific nature to Transmission, so when displayed, the room becomes its own vault – tuned only to hold this composition.

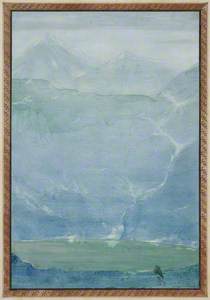

2000s – Zarina Bhimji

Zarina Bhimji was born in Uganda to Indian parents, moving to Britain in 1974, two years after the expulsion of Uganda's Asian community under Idi Amin. This migratory experience is weighted by complex narratives of nationhood and nationality and, as a result, her film, photography and installation practice takes a non-linear approach to histories and geographies. Both India and East Africa are important locations in Bhimji's work.

The 2000s marked a transformative period for Bhimji, with her participation in 2002's Documenta 11, curated by Okwui Enwezor, cementing her role in a global postcolonial discourse. In 2007 she was nominated for the Turner Prize.

The 2007 photograph Shadows and Disturbances, part of the Government Art Collection, was taken as research for her film Yellow Patch (2011), which draws on the history of migration and trade across the Indian Ocean.

© Zarina Bhimji. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: Government Art Collection

Shadows and Disturbances (edition 2/4, plus two artist's proofs) 2007

Zarina Bhimji (b.1963)

Government Art CollectionThe film focuses on crumbling architectural exteriors of colonial period private and public structures in India to meditate on absence and the residues of administrative, civic and communal life.

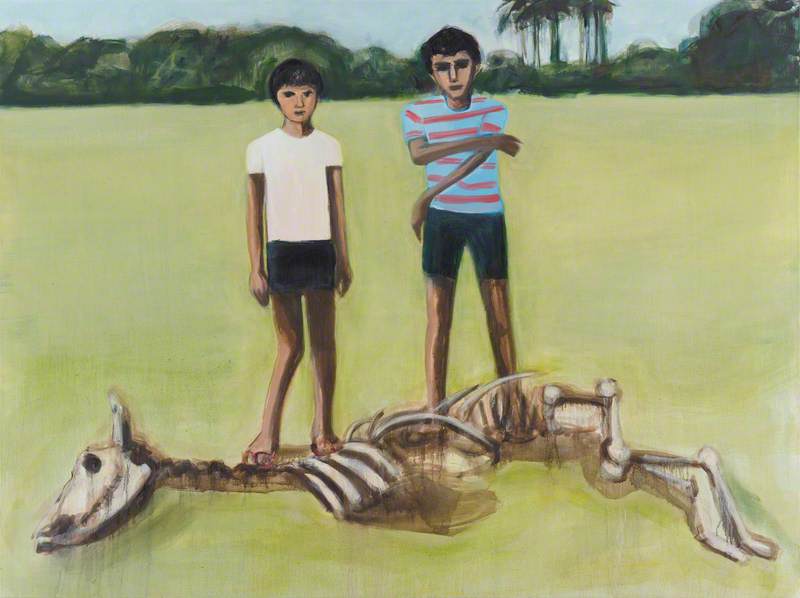

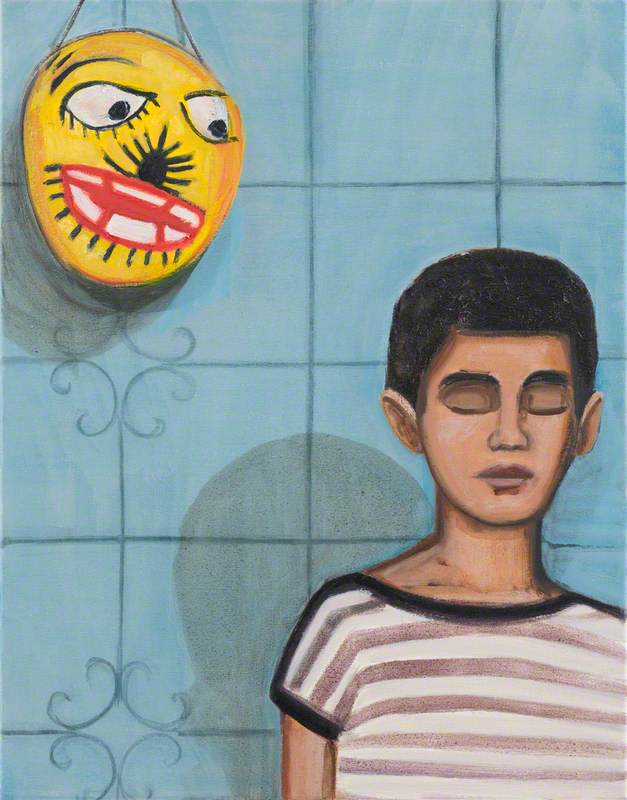

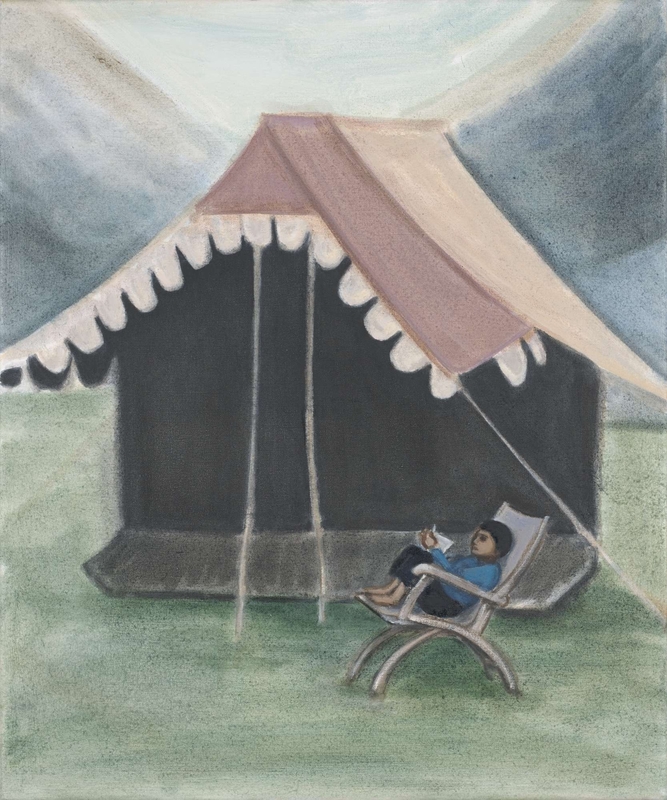

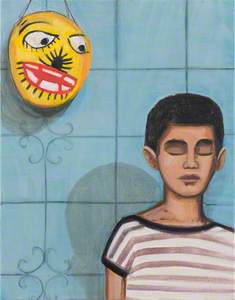

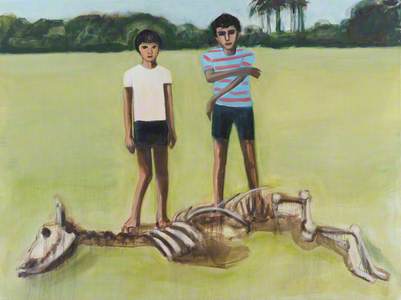

2010s – Matthew Krishanu

Matthew Krishanu's work captures the intersections of faith and memory, often exploring the landscapes of his upbringing in Bangladesh alongside his experiences in Britain – he was born in Bradford before moving to Dhaka and he studied in both Exeter and London. His paintings hold a mighty intimacy, with brushstrokes and a colour palette that contribute to the open-ended nature of his scenes.

Ordination (2017) reflects Krishanu's recurring engagement with themes of religion and family. Depicting a clerical figure surrounded by subtle symbols of ritual and belonging, the work hints at Krishanu's personal connection to missionary life through his father's role as a priest in Bangladesh. You can read an interview with the artist in this story.

2020s – Jasleen Kaur

Jasleen Kaur won the 2024 Turner Prize with Alter, Altar, an installation of everyday objects which draw on her own upbringing as part of a South Asian family in Pollokshields, Glasgow. Many of the altered objects represent personal and communal connections: photographs of family and community action, a harmonium emitting a mechanically induced drone, and a red Ford covered in a doily – a replica of the car her Dad first drove when he arrived in the UK.

View this post on Instagram

These are situated under a hanging Perspex sky with objects remade from Kaur's life printed on top, such as a tracksuit the colour of Irn Bru featuring the words 'Can't do it', a football scarf and lottery tickets. The objects act like clouds, evoking the idea of looking up to the sky for hope and guidance, when the sky is not yours.

The installation shows the intangible safety nets that can be stitched together through the shared experiences of spirituality and solidarity that communities have created in order to exist within oppressive structures. This is is at the centre of much of Kaur's practice: her Turner Prize acceptance speech evoked deep empathy for the suffering in Palestine and highlighted how the arts can better respond to experiences of oppression.

He Walked Like He Owned Himself (2018), part of the collection at Touchstones Rochdale, reflects the quiet defiance of individual presence as an act of self-ownership, capturing the resilience of those who navigate and resist systems of control. Kaur's practice, rooted in empathy and multiplicity, redefines what it means to create art in dialogue with lived struggles, dreams, and solidarities.

For reasons of length, this article had to omit many other artists, geographies and experiences. As such, it is a snapshot of South Asian artists working, living or born in Britain over the last century. The diversity of backgrounds and nuance of themes reveals how hard it is to provide a clean narrative for the sake of balancing or addressing representation. Perhaps the geographical label of 'South Asia' is problematic in this artistic context, despite the obvious threads of connectivity between artists.

Hassan Vawda, Doctoral Researcher at Goldsmiths/Tate

This content was sponsored by Jerwood Foundation