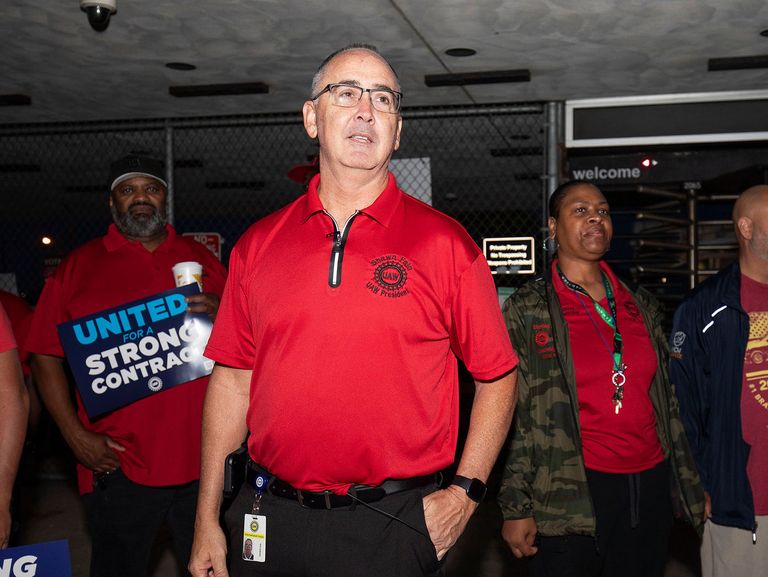

It all started with a handshake, or at least it was supposed to. For as long as anyone can remember, contract negotiations between the United Auto Workers and Detroit’s Big Three have kicked off with a ceremonial handshake between union leaders and the CEOs of GM, Ford, and Chrysler (now Stellantis). A genial show of decorum. This past July, though, Shawn Fain, the newly elected president of the UAW, wanted to set a different tone.

Standing in front of a news camera outside a plant before a meeting with CEOs, Fain announced he was snubbing the traditional make-nice. “We don’t see a reason to shake hands,” he said before cataloging what he decried as two decades’ worth of unfair contracts, abusive treatment, and gross inequity. Leaning forward, in sharp-rimmed glasses and a buzz cut, Fain continued, growing visibly more agitated as he went on. “I hear some of the CEOs talk about ‘Our workers are like family.’ That’s nothing but a lie.”

As an opener to a parley it was, to borrow a line from Braveheart, rather less cordial than the auto executives were used to.

“I just felt it wasn’t right to walk into a room and shake hands with people that weren’t treating our members right,” Fain explains now in a video interview. “The big thing I was trying to do is change the narrative.” From the moment he took office last March, Fain has marked a stark departure from recent generations of UAW leadership. He staked out an aggressive contract position and signaled hard that the union wouldn’t shy away from a strike if terms weren’t agreed to by the September deadline. Steve Rattner, Obama’s car czar, in an op-ed in The New York Times, called the union’s demands “overly ambitious” and labeled it “militant.” Fain didn’t back down, and as the deadline approached, he contemplated doing something that had never been done before in the annals of American labor: a simultaneous strike against the Big Three auto companies.

Now rounding out his first year in the job as head of the 400,000-member UAW, Shawn Fain finds himself in the vanguard of a resurgent and reinvigorated American labor movement. Last year saw parallel strikes by Hollywood’s actors and writers unions. The Teamsters negotiated major concessions from shipping giant UPS after authorizing a strike and practically daring the company to call their bluff. And workers at Starbucks and Amazon made headlines with their determined efforts to unionize.

But the clearest indication of a major shift was the UAW’s strike, an audacious and risky move that surgically targeted specific plants of all Big Three companies at once in an escalating action designed to put increasing pressure on executives to bargain. The strike lasted six weeks, and in the end the union won a 25 percent pay increase over four years and other significant concessions that would have been hard to imagine only a short time ago. More to the point, polls found that a majority of Americans supported the autoworkers, a sea change in public opinion in the decades since Ronald Reagan fired thousands of striking air-traffic controllers in 1981. In contrast, President Biden made a show of appearing alongside striking UAW members in front of a plant in Michigan in September—the first time a sitting president has ever joined a picket line.

Why now? What changed? “I think last year was a culmination of years of frustration,” Fain, 55, says in a mild Hoosier drawl. “You look at the last 40 years in America—people have been working longer hours and multiple jobs and not getting ahead. Then 2020, with the pandemic—I think that was a real eye-opener, a time for working-class people to analyze what was important in life. I think most realized what was important wasn’t working seven days a week, 12 hours a day to live paycheck to paycheck.” Fain believes the pandemic helped labor rediscover its most fundamental negotiating tool. “When it hit, many of the workers in the fast-food industry said, ‘I’m not gonna leave my house and risk my safety for $10 or $12 an hour.’ And what happened? Fast-food companies like McDonald’s started raising wages to $20 an hour because they couldn’t get anyone to come to work. So I think that was a great lesson for all of us in the working class about the power we have if we withhold our labor.”

This article appeared in the April/May 2024 issue of Esquire

SUBSCRIBE

It was never Shawn Fain's ambition to be president of the United Auto Workers. To hear him tell it, it wasn’t even his ambition to be a union rep when he started out as an electrician at the Chrysler plant in his hometown of Kokomo, Indiana, 30 years ago. He calls what happened “a migration,” which for him seems to have entailed little by little growing more and more pissed off, and more and more involved. “I didn’t like the way some things were going in our plant, so I ran for a position there.” He served as a committeeman and shop chairman for his local, opposing the 2007 introduction of a tiered wage system, which started new workers out at lower rates. The concession helped motivate him to join the UAW negotiating team in 2009, where he gained a reputation as a dissident and a hard-liner. He moved to Detroit for a UAW staff job in 2012.

Participating in bargaining as the industry was emerging from the 2008 financial crisis was formative for Fain. “Watching things turn around really quickly for these companies and then watching them realize record profit after record profit, year after year, and continue to abuse the tier structure—that’s why I’m here right now.”

That and executive pay. The Big Three “made a quarter trillion dollars in the last decade, and CEO pay went up 40 percent in the last four years while our conditions went backward,” he says. Members’ cost-of-living increases were suspended, their benefits reduced, and the hated tier system meant that new workers earned less for doing the same job.

It culminated one day in the summer of 2022 when Fain found himself looking in the mirror, contemplating running as an insurgent reform candidate for president in the first direct elections the UAW had ever held. Previously, presidents had been chosen by delegates at a convention, but a series of corruption scandals led to a referendum and a switch to a direct election, overseen by a federal monitor.

“I remember just saying, ‘If you don’t do anything, are you going to be able to look yourself in the mirror ten years from now and be happy with that?’ And I knew I wouldn’t.” He also knew that it was all or nothing. “I was either going to be president or I would be sent back to my plant if I didn’t win. And I was okay with that.”

The resulting margin was razor-thin—fewer than 500 votes—but Fain won office.

Fain's migration, as he calls it, seems ongoing. In public remarks, and in our discussion, he is drawn to the larger and larger view, and to the overarching problem of vast income inequality. “We don’t just have an obligation to our members,” he says. “This is our generation’s defining moment. When you have the situation where a handful of billionaires have as much wealth as half of humanity, we have a crisis on our hands. We have to ask ourselves, what kind of country do we want? What kind of world do we want?”

In January, the UAW endorsed Joe Biden for reelection, and Fain really gets going when talking about Biden and Donald Trump. “Joe Biden has a history of standing with working-class people, while Donald Trump has a history of serving himself. On his so-called reality-TV show, The Apprentice, or whatever the hell it was, his favorite words were ‘You’re fired.’ ” Fain is particularly incensed about the vilification of migrants at the southern border, in which he sees a clear ploy to divide working people. “I listen to this stuff about border security, and it’s garbage to me. People trying to cross a border because they’re trying to find some semblance of a life are not a threat to us.” In migrants he sees himself. “All four of my grandparents came from the South during the Great Depression. To say our family came from poverty is an understatement. So I look at people trying to cross the border and I see my grandparents. The only difference is my grandparents were born in the United States—they migrated north to find a life.”

Being from Indiana, Fain is a basketball guy. He was a shooting guard in high school and has a goal in his driveway, where he still does a few drills in the summertime, for exercise. He has John Wooden’s Pyramid of Success hanging in his office—“Wooden was a fellow Hoosier, from Martinsville.” Near its apex, the pyramid lists “Enjoyment of a difficult challenge.”

Coming off the success of its new contract, Fain’s UAW appears to be seeking difficult challenges. It’s looking to expand from its traditional foothold in the Big Three and organize workers in more than a dozen nonunion plants owned by companies like Volkswagen, BMW, Mercedes, Toyota, and Honda, most located in the South, which is largely hostile to organized labor. The UAW has made surprising inroads. It has collected signed union cards from more than half the workers at one VW plant in Tennessee, for example. But organizing in states with “right to work” laws will be a hard fight.

So will Fain’s most far-reaching effort. Late last fall, when announcing the UAW’s new contracts with the Big Three, he pointed to the expiration date for the four-year agreements—the day before May Day 2028. And he called on leaders of other unions to recalibrate their own contract cycles to sync with the UAW’s. The implication was clear: Fain was hinting at the leverage of a general strike, involving multiple unions, across many industries. Just like his simultaneous actions against the Big Three, only much bigger, the stakes much higher, the risks much more perilous. If that day comes, it’s a good bet Fain won’t be shaking any hands until a deal gets done.

Reorganized Labor

Three more key figures from the new wave of American union leadership:

FRAN DRESCHER

The former sitcom star was perhaps underestimated when she won election to head the Screen Actors Guild in 2021, but when push came to shove, she didn’t hesitate to lead actors off sets last summer in what became the longest strike in SAG-AFTRA history. Drescher won wage increases, protections against AI, and residuals for streaming.

LIZ SHULER

The first woman ever to head the AFL-CIO was a protégé of Richard Trumka’s and succeeded him as president of the 12-million-member labor federation after his sudden death in 2021. Shuler has called on unions to lead a fight against AI and its potential to replace human labor.

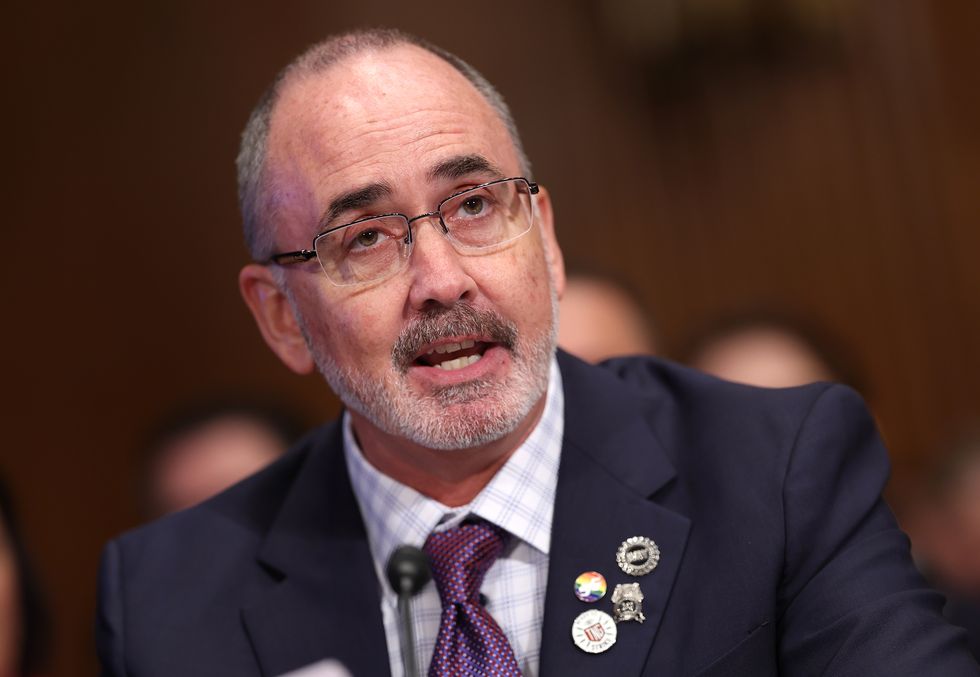

SEAN O’BRIEN

Since taking over the Teamsters from Jimmy Hoffa Jr. in early 2022, O’Brien has been savvy about using social media to bring the union’s agenda to the widest audience. His high- profile Twitter/X smackdown with Republican senator Markwayne Mullin nearly resulted in a real-life smackdown in a Senate hearing room.